The only thing we know for sure is that Hip-Hop started on Sedgwick Ave in the Bronx in 1973. After that, things are iffy. Some say that when they heard “Walk This Way” from Run DMC and Aerosmith, the genre bended toward its infinitely upward trajectory. And then, with the releases of both Midnight Marauders and Enter The Wu-Tang (36 Chambers), some people consider November 9, 1993 the last day of pure Hip-Hop. All of these dates, including the first one, are somewhat unofficial so I’d like to submit my own date to Hip-Hop history and see where it lands.

On September 29, 1998, the day that Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life, The Love Movement, Mos Def & Talib Kweli Are Black Star, and Aquemini were all released, postmodern Hip-Hop was born.

Now, the phrase “postmodern Hip-Hop” is super loaded (and also some shit I sort of made up), I know, and since it’s probably harder to explain the latter half of that phrase, I’ll start with post-modernism itself.

Generally speaking, postmodernism is a late 20th-century artistic concept (mostly music, in this case) that greets modernism (all Hip-Hop music until this day, 22 years ago, in this case) with broad skepticism, subjectivism, and a general suspicion of reason. Basically, anything that fucks with the way we collectively view something we previously thought was “unfuckwithable” is postmodernism. Eh, that’s a little too general probably, walk with me.

Think about the semi-recent concept of minimalism, in stark contrast to the “more is better” cultural ethos most of America has subscribed to for years. Or Pulp Fiction, a movie that reveals its plot non-linearly. Or even a dad-joke that’s funny simply because its “not funny”. This is postmodernism, and it exists everywhere. But for Hip-Hop, it wasn’t always there — well, not until September 29, 1998 that is.

And it was these four albums that sparked it:

Now, we know good things come in two’s, and three’s; but as far as I’m concerned, if some is good, four is better. Let’s get it.

Vol. 2… Hard Knock Life — Jay-Z

This album is what put Jay-Z on the map as a perennial big player in the game. A game that had undoubtedly already seen his amazing, albeit raw, Reasonable Doubt, as well as his underrated, even if a bit despondent, In My Lifetime, Vol. 1 albums. More than anything, however, this was a game that was thirsting for someone to fill Biggie’s shoes.

Jay-Z made a strong effort to graduate from the streets for the first time and really tear up the billboards. In many ways, the crater that Biggie had left the year prior was filled by him here. And with songs like “Money Ain’t A Thing”, with Atlanta’s Jermaine Durpi, “Can I Get A”, featured on the Rush Hour soundtrack, and a monster sample on “Hard Knock Life”, he was able to win Best Rap Album at the Grammys, surprisingly the only time he’d do so.

So, yes he filled up the charts just like Biggie did, but he did it with a lot more skepticism and disdain toward how we’d all been taught to engage with rap stars and digest their work.

He could never lose his accent, but he certainly started talking, dressing, and acting a little different here — and with that, he was more than NYC, he was postmodern Hip-Hop. And if one of the hottest rappers in the game, from the then-undisputed epicenter of the game, was cool with it, everyone else had the license to follow him. If Biggie’s death had any positive affect on Hip-Hop, it was that artists like Jay-Z could make a new mold without having to break the old one — and that started with the realization that Hip-Hop was everywhere, not just NYC.

🧠 What we learned: Postmodern Hip-Hop is not regional.

🤯 Crazy, Runaway Thought: Who knows, if Biggie doesn’t die, and rap is still NYC-centric, maybe Big Pimpin’ would’ve been made with the Ruff Ryders the following year, and not UGK.

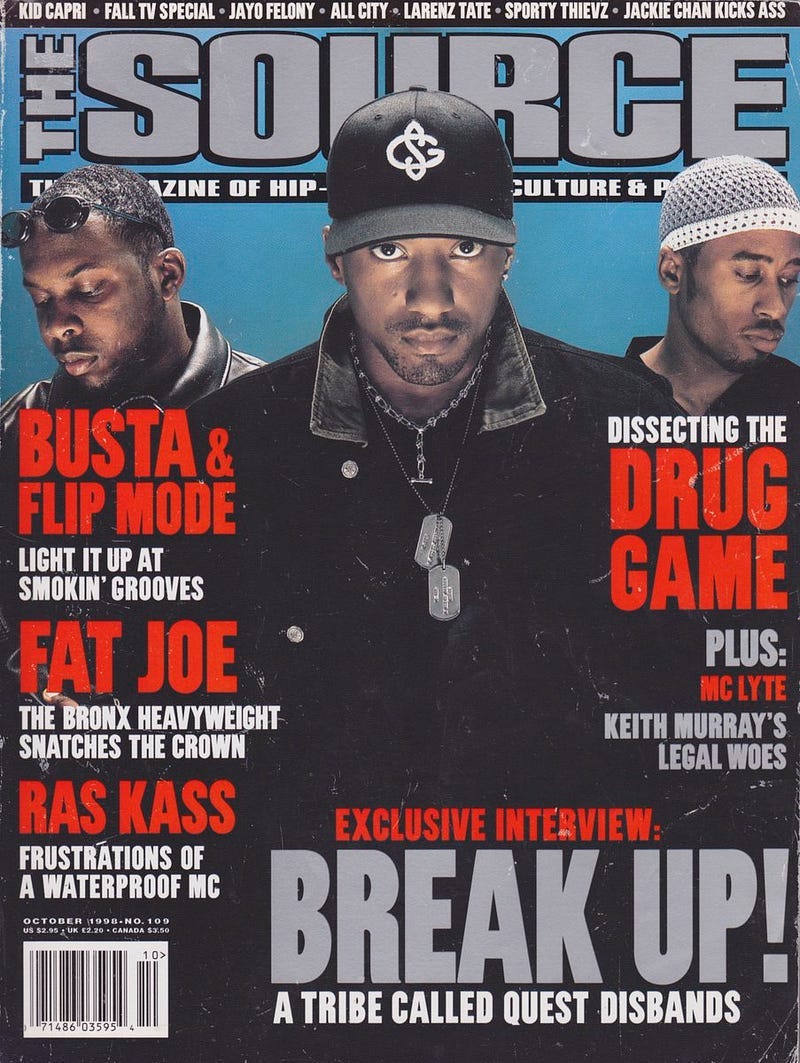

The Love Movement — A Tribe Called Quest

I believe that true greatness has no size, shape, formula, etc… but it does have an expiration date. And in ATCQ’s case, it was 9/29/98. The irony? The same purist (read: modernist) era they’d help create and flourish, all throughout the decade, is what they found themselves running from in the end. They wouldn’t make it past this date as a group, but whether they knew it or not, they took out the door with them an era of rap that couldn’t co-exist with what was to come.

On this date 22 years ago, ATCG was arguably (read: absolutely) the best group in Hip-Hop history (and they still are!… arguably). But the reason we can say that is because they rode off into the sunset when they needed to, regardless of how upset people were at the time. I mean, it’s not like they couldn’t have made an extra album or two, but, ultimately, they didn’t want the last check they ever wrote to bounce, and I feel that.

And, on that note, this album did have a little bounce. The Tribe will always Find A Way, even if they can’t Move It Along like they could on their ’90 debut. This was their fifth studio album in nine years, no small feat, but some would say they maybe should’ve broken up an album sooner. Ultimately, though, it happened this way.

Luckily, it was just a “see you later” for both Q-Tip and Ali Shaheed Muhammad, who were both back on the scene almost immediately, separately this time, and with completely different sounds (“Vivrant Thing” and Lucy Pearl, respectively). Also, shoutout to Phife’s 2000 Ventilation: Da LP while we’re here.

Ultimately, it wasn’t that that they were no longer Hip-Hop, it was that together, they’d changed the game into something they could only traverse apart.

🧠 What we learned: Postmodern Hip-Hop is not to be dominated by groups.

🤯 Runaway Thought: Who knows, If ATCQ had broken up after their 1996 album instead, and Q-Tip was focused more on his production, Q-Tip might have been the one to sign Kanye West.

Mos Def & Talib Kweli Presents Black Star — Mos Def & Talib Kweli

Now you know, the death of one amazing group couldn’t happen without the birth of another. The music gods aren’t that cruel. I mean, the basketball gods gave us Lebron the same summer MJ retired.

Ok — this was the only album from this duo, but it’s all we needed. And to be clear, this was not ever the second-coming of Q-Tip and Phife Dawg, or Eric B. & Rakim, or Gang Starr or nothing like that. This was their own thing — a vital part of a larger theme that saw the genre expanding itself, within itself. Growing closer to the groundwork that made its music so infectious to begin with.

It was everything we’d come to love about Hip-Hop. And, in an almost direct ode to postmodernism, they’re giving us that gritty 36 Chambers street shit, the Midnight Marauders jazz rap, and merging them in such an enlightening and new way that we can’t help but smile at Mos’ take on Slick Rick (and Snoop’s) “Children’s Story”, or Talib’s “B Boys Will B Boys” blast from the past.

It was gritty and groovy; musically-rooted in jazz, boom bap, charisma and chemistry. Perhaps most memorably, though, it was educationally transformative, leaning on themes of Marcus’ Garvey’s Pan-Africanism and unafraid to talk Black as they moved past the old guard.

After this, they both went on to have separate solo careers, but still regularly appear on each others’ projects. While Mos Def’s solo efforts have made room for postmodern genre favs like So Far Gone, The Love Below, Coloring Book, 2014 Forest Hills Drive, and Igor, Talib’s style has influenced acts like Lupe Fiasco, Kanye West, Kendrick Lamar and even Common.

They, too, needed to be separate in order for postmodern Hip-Hop to thrive, and all in all, I guess I’m happy about that too.

🧠 What we learned: Postmodern Hip-Hop is formless.

🤯 Runaway Thought: Who knows, if they’d done another album together, and not focused on their solo careers, we may have ended up seeing them as just another Camp Lo.

Aquemini — Outkast

This is the most critically acclaimed album on this list, and of course my personal favorite, and what originally sparked the idea of this piece. Like Jay-Z, this was their third time around the block — but unlike Jigga, they sort of already had their style. They were orbiting in space in their own unique ellipse, just waiting for their style to collide with the ears of the stingy Hip-Hop gatekeepers of the time.

The dirty secret is they’d been making postmodernist music the entire time. It wasn’t until the the tastemakers (some of whom are listed above) began to chip away at the overarching modernist construct we’d grown to love, that we could see the beauty of what was to come: Liberation.

Remember, their debut album, Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik, only received 4.5 mics from The Source (something Big Boi raps on this album, and part of the reason Andre was so intent on the South “having something to say”) so they had some boulder-sized chips on their shoulders here. They came in with something major to prove to a genre that had an even bigger language-barrier.

So, what did they do? Doubled down and kept doing them. They helped bring in postmodern Hip-Hop by simply being postmodern Hip-Hop. They were already going against the grain, unconvinced that the way things were going was the way they should be. The secret sauce was simply their will to keep it up.

You know that phrase “you become what you fear”? Well, this is what happened to Hip-Hop on this day it seemed, because no matter how different these dudes sounded at the time, Aquemini was undeniably blood of Hip-Hop’s blood, and flesh of its flesh… from the front all the way to the back of the bus.

And, of course, it got all 5 mics this go around (the first to do so from The South) cementing the album, their style, and this day in Hip-Hop history.

🧠 What we learned: Postmodern Hip-Hop is unapologetic.

🤯 Runaway Thought: If Outkast had received the credit they deserved for their first album in ‘94, they’d have had less to prove for themselves, and maybe The South, and then somebody like Ja Rule would’ve eventually made an album called Trap Muzik.

So yeah, you might think this is horse shit but whatever, it’s real y’all. Sometimes it takes time to accurately judge a moment. That’s why time is the undefeated great equalizer, and hindsight is 20/20.

It is of no coincidence that these folks are some of the best to ever do it and are all my favs. To be honest, I never really had a choice — I grew up to postmodern Hip-Hop. I’m sure they had no clue what was going on that Tuesday in 1998, and if they did, they might have messed something up. This was perfect as is, and 22 years later, I’m thankful that it happened just the way it did.

From the stylistic skepticism, inclusive subjectivism, and your unapologetic suspicion of reason, all of you helped us fly unabashedly into the space we orbit today. I wonder if there’s another September 29, 1998 coming, or if this date is one of a kind? Maybe it’s happened already and we just haven’t had enough time to notice yet?

Only time will tell.

For Lack of a Wetter Bird, September 28, 1998 is the day postmodern Hip-Hop was born.